The Southern Highlands of Tanzania are located in the southwest portion of the country, beginning at Makambako Gap and continuing into Malawi in the south. Visitors heading towards Malawi or Zambia often travel through these parts, admiring the impressive mountainous and volcanic scenery and stopping off to enjoy the brilliant hiking opportunities.

This area of the country is also home to Ruaha National Park; a fantastic place for a safari and particularly well-known for its elephant population. If you want to opt for an alternative to the classic Tanzanian holidays in the north of the country, the Southern Highlands are a brilliant place to visit.

Ruaha National Park

The wide distances of Ruaha National Park have a drama and atmosphere quite unlike any other Tanzanian park.

Here the land has its own kind of remoteness that seems to emanate through time itself. It is an ancient place in the valley of the Great Rift, where mile upon mile of sandy red earth feels worn and bleached by an age-old sun, and the hilly distances are punctuated with distended elephant-battered girths of countless massive baobabs that live for a thousand years.

Such a charismatic combination of ochre-red earth, pale russet grasses and the parched paths of wide sand rivers appeal to all old preconceptions of an archetypal African land.

Part of the present-day attraction of Ruaha is its distant location, which demands a long drive or an expensive flight to get there. This means that the park is consequently hardly visited by tourists, and major tracts of the landscape are still largely inaccessible.

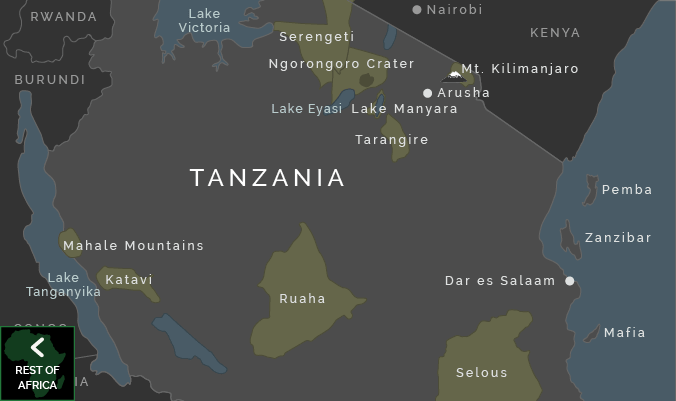

Covering 10,300 sq km, Ruaha is the second largest National Park in Tanzania, after the Serengeti. It flows down from the high plateau around the Njombe River in the northwest and then slopes across a wide valley to the Great Ruaha River in the southeast.

Such a vast and fascinating landscape makes it an ideal location for a longer safari, with between four and seven nights recommended, not least to make the flying costs worthwhile. There are presently just two alternatives for permanent accommodation within the National Park, each run by brothers who explored this land as children, but two other sites have been awarded for semi-permanent development to The Selous Safari Company and Coastal Travel.

Trips to Ruaha are often combined with the Selous Game Reserve, as the two locations are entirely complimentary for their differences and part of the same scheduled flight route.

History of the Ruaha National Park

Ruaha National Park was originally a part of the Rungwa Game Reserve until it was classified as a fully protected National Park in 1964. It now forms an important component of the massive 30,000 sq km of the protected ecosystem that covers Rungwa, Kisigo and Ruaha.

Ruaha National Park is named after the Great Ruaha River – and the word Ruaha is the Hehe tribe word for ‘Great’. In the late 1970s and early 1980s dams were created at Kidatu and Mtera to use the strength of this river to power the majority of the nation’s hydro-electricity – yet many visitors to Ruaha during the dry season today might be a little disappointed when their experience of the Great River is just a meandering trickle, even if it does concentrate the wildlife around the remaining pools.

Until recently, the Great Ruaha was never known to run dry, barring one occasion during a serious drought in the late 1970s. But recently, the Great Ruaha has been drained dry in areas of Ruaha National Park for two consecutive years.

Its power and might as a perennial water reserve have been depleted by agricultural practices and certain rice-growing initiatives upstream. These are responsible for reducing the quantity of water and creating a present situation that is near-disastrous – especially for the serious ecological threat that it presents to the resident variety of wildlife.

The river fish population has already suffered, and crocs and hippos are forced to squeeze into smaller, more rarefied patches of water. Having flourished in the wet season until the waters dry and shrink off, the new situation has given the whole park the nature of an annual round of musical chairs.

Since a bridge was built across the Great Ruaha nine years ago, Ruaha National Park has experienced a seasonal transformation, with access no longer limited to the dry months. It is now possible to enter the park all year round, although the River Lodge and Mwagusi close for a couple of months during the long rains in April and May.

Wildlife in the Ruaha National Park

The joy of Ruaha is that there are hardly any people there at all. Instead, a variety of heavy-duty wildlife lays claim to its hilly savannah and bush.

Ruaha has one of the greatest elephant populations of any African national park, and the dry, open hillsides encourage antelope and buffalo to gather into protective large herds. This terrain is particularly good for seeing predators, especially lions and potentially leopards, as well as packs of African hunting dogs.

The many rivers and swamps around the Ruaha River are also alive with huge numbers of hippopotami, crocodiles and fish, and the many giraffes and zebras that roam the plains make their way to the shores of the water to drink.

Ruaha is the only east African park with both Greater and Lesser Kudu and sable and roan antelopes, and, like the Selous, has an unusual combination of East and Southern African wildlife and birds. The Red-billed wood hoopoe, Violet-crested Turaco and Racquet-tailed roller are among the many coloured migrants and just a small selection from the 480 species of bird that have been sighted within the park.

The wetter months during the first third of the year are the best months for bird-watching, and the beauty of the park is enhanced by the blooming miombo woodland flowers. The miombo woodlands are dominated by 15 species of Brachystegia trees, while the rolling grass plains are covered with various acacias, spiny Commiphora and plenty of baobab trees. Around 1,650 plant species have been identified within the park, the majority of which flower.

In recent years, poaching has been a serious problem in Ruaha, decreasing the famously huge population of 22,000 elephants recorded in 1967 to only 4,000 in 1987. This still represents one of the largest populations in any African National Park, and it is more heartening to know that numbers have recovered up to 12,000 during the last decade as a result of the Park’s very successful anti-poaching action, which has made exemplary efforts to involve local communities.

The result of this serious dent in the elephant population now means that fewer mature animals have grown to full size (usually around 60 years of age), and it is rare to see any elephant with a fully developed pair of tusks.

These days it is more common to come across tuskless and small tusked elephants, once an anomaly and yet now represented in a far higher proportion since these survived the brutal culling. This often inspires ruminations on the miracle of natural selection, but it remains to be seen whether future generations will breed a larger proportion of small tusk and tuskless elephants, or whether the large tusk gene that produced the 8ft tusks plundered by the ivory traders will prove dominant once again.

It is more encouraging that the elephants in Ruaha are still breeding enthusiastically and a large number of female elephants around the park can be seen with babies.

The animal’s longevity and intimate social structure are complex and they have been proven to be highly intelligent animals. They show collective grief over death within their groups, often gathering around the dead elephant, and may try to carry the body away.

It remains surprising how the Ruaha elephant populations do not show great signs of nervousness around humans, considering the brutal culling that has occurred here.

Baobab Trees in the Ruaha National Park

The vast and bizarre features of the baobab tree are striking and iconic features of the African bush. Of all the eight species of baobab worldwide, the African variety, Adansonia digitata, is the largest, and the most impressive.

While these trees may inspire a certain awe in most passers-by, they represent a deep-rooted significance in the lives of those people and animals that live around them. The baobab is brimming with life-giving properties that are nutritional, medicinal and practical, and consequently, it has earned a popular reputation for being an important, even spiritual tree.

Every part of the tree can be put to use; the fibrous, stringy bark can be largely stripped, without killing the tree, and used for string, rope, fabric and netting. Various parts of the tree are used for medicines, to reduce malarial fever and relieve eye infections, gum diseases, boils, burns and dysentery to name but a few, and the fruit has such a high vitamin C content that it is popularly used to combat symptoms of scurvy.

A drink made from the bark is said to make a person strong, and one made from the soaked baobab seed has a reputation to protect the drinker from crocodiles. The trunks and cavities store water that enables them to survive in dry areas through the hot summer months, and thirsty elephants batter the trunks to plunder their supply.

The baobab can sustain an amazing amount of abuse and will continue to flower and function even when elephants – assisted by zebras and giraffes – have chewed a hole right through their middle. They live for generation after generation of human life, continuing to grow for 800 years, and some say even up to 2,000 years.

The trees become the focus of rural village life, as their broad branches and tangled roots provide a naturally comfortable and shady communal area and their longevity ensures their historical place in the community. The massive trunk can grow a circumference of up to 25m round and often becomes hollow, and this area has been used across southern Africa to provide a spiritual tomb for chiefs and a home to many unknown spirits that are widely believed to inhabit their peculiar gnarly forms.

Mbeya

The landscape all around Mbeya is cracked and pitted with a staggering variety of strange and fabulous formations. Beyond Makambako town, the Mbeya region becomes green and mountainous to the south.

Here the eastern arc of the Great Rift Valley almost meets the Mbeya range, which extends in a north-westerly arc, rising up beyond Mbeya town and crowned by the glittering quartz-crystalline silhouette of Mbeya Peak. South of the town, the Uporoto Mountains form a dense and fertile region punctuated with volcano-top villages, waterfalls and blue circles of crater lakes that range all the way down to the shores of Lake Malawi.

To the east of the town is Mbeya Plain, stretching out to the Safwa scarp and the great flat-topped mountain of Ishinga, all shaped by time from a vast expanse of sandstone layers. In the midst of all lies Mbeya town, the third largest town after Dar and Tanga, a sleepy but still thriving metropolis that has grown from a now abandoned government gold mining station established in 1927.

The town has developed in industrial pursuits, and although it is not the prettiest place, the surrounding area is very peaceful, with exciting natural landscapes and interesting homesteads and coffee farms to discover by car or on foot.

History of Mbeya

The most recent serious volcanic activity to shape the Mbeya-Iringa region occurred between 20 and 4 million years ago as a result of the rift action between underlying tectonic plates. As a result, this region presents a wide spread of mountains, crater lakes and lava or ash plains, with a mass of natural interest throughout.

The open plain between the Eastern Arc mountains and the Mbeya range was converted into a research station in 1927 to assess the potential for mining gold in the area. The rifting faults of the surrounding mountains certainly appear to contain a wealth of riches, but what glitters here is less often gold, as most of the exposed strata of these mountains are composed of quartz crystals sparkling in sunlight.

The Lupa goldfields north of the town became a goldrush region in the 1930s, but were then closed a couple of decades later. Panning continues here today on a very small scale, in the form of local backyard industry, and is occasionally rewarded by a small granule of gold.

The continual growth of small industries has supported the expansion of the town since then, particularly commissioned work on the road and railways.

Finding Guides in Mbeya

While it is possible to arrange guides to lead you on walks and days out in this region, there is an extremely well-recommended and worthwhile organisation in town that provides reliably informative and friendly guidance and assistance.

Sisi Kwa Sisi is a locally run initiative managed by Nico Ntinda and Felix Amndo, who have a shared reputation for being ‘lovely’. They will meet travellers from the train or bus station, and arrange and accompany them on walks and excursions around Mbeya for a very reasonable price and their travel expenses.

They speak good English themselves and are teaching other local guides as their enterprise expands, and you can find their offices at the bottom of the hill near the bus station, beside the roundabout with the rhino sculpture. Local guides are very worthwhile to have around for the benefit of translating more interesting Swahili exchanges as you explore. They can also arrange for you to visit local traditional healers or visit rural villages, and are helpful in light of recent security concerns for tourists wandering the outskirts of Mbeya unaccompanied.

What to Do in Mbeya

Hiking

There are an endless number and combination of walks in the mountains surrounding Mbeya, with landscapes and unusual attractions to suit all time schedules and energy levels. A couple of spare hours can be well spent on the outskirts of town, enjoying a good circular walking route that leads into the forests to the north of the town and provides panoramic views back over Mbeya along the way.

Head northwards to the top of Lupa Way until it crosses over Kaunda Avenue, turn right and almost immediately left onto a cul-de-sac and follow the pathway at the end to the top of the hill. This leads through a forest of eucalyptus and wends its way along a ridge at the base of Loleza Peak, which stands 2,656 metres high above.

Halfway along the side of the ridge, fork right and head for a mature pine forest, crossing the stream as you go. Continue through the pine trees to the track, turn right and then right again when the path divides. This will lead you back onto Kaunda Avenue and finally Lupa Way via Nzowa Road.

Birdwatching

This whole Mbeya region is awash with hundreds of species of bird, even in Mbeya town where Fiscal shrikes, Robin chats and Tropical Boubous can often be spotted or heard, or various hornbills such as the black and white Silvery Cheeked and smaller Crowned hornbills.

Birdwatchers will find many more species to delight them on the Usangu Plain, ranging dramatically in size from long-legged families of ostriches to turkey-sized secretary birds and a colourful array of equally charismatic smaller birds such as the Yellow Collared Lovebird or the Paradise Whyder, or Beautiful Sunbirds.

An amazing array of waterbirds can be found on the crater lakes around town, such as the Ngozi Crater lake. These are always home to small water birds such as the yellow-billed duck, the little grebe and more curiously, the Red-knobbed coot.

Around Lake Nyasa, the Fish Eagle, open-billed stork and amazing balancing African Jacana can often be seen, along with swift flying Grey-headed gulls and Darters.

The mountain forests, such as those around Ngosi and Rungwe craters provide an entirely different environment in which to find birds, although the density of the undergrowth does make them much harder to spot. One of the most popular and colourful is the small and delicate Bar-tailed trogon, or perhaps you might glimpse another brilliantly coloured bird with a shining blue head and green back and a distinctive yellow belly – the white-starred forest robin.

Both of these are quiet little bough hoppers, but can sometimes be seen if not heard when the watcher is patient and still.

The Mbeya Mountains

The most magnificent peak towering above the many around the town is Mbeya Peak, which stands at 2,826 m high. Walks up Mbeya Peak and through the surrounding area can be arranged through Utengule Country Hotel.

Although the route up is said to be steeper than the ascent of Kilimanjaro, it presents excellent photographic opportunities across the wide African savannah on one side and a patchwork of fields on the other, especially at dawn

There is more than one way to climb this mountain, and the easiest of these begins with a fantastically scenic drive along the road towards the now near-desolate gold rush town of Chunya. This town was the centre of the last gold rush during the 1920s and 1930s, and a 3,000-gram carat of gold was reportedly found here at the height of its fame. Remains of the old mines can still be seen, and occasionally this dusty old town receives a brief revival of gold-panner interest.

For the mountain, follow the road for about 13 kilometres out of Mbeya, until you reach the sign to Kawetire Farm, after which a left turn heads west through the forest plantations. Follow this road under Loleza Peak past two villages until you reach the end of the driving road and a mature pine plantation.

Ensure your vehicle is safe, even guarded, and then follow this track on foot to the ridge, where you head right then across the saddle to the peak. Low-grade garnets can be found along this way, and fantastic views are afforded from the top if the weather is good.

Continuing northwards along the Chunya Road brings you to excellent hidden picnic spots, such as the World’s End Viewpoint at the end of the track leading to Chunya forest, with stunning views overlooking the Usanga Plain beyond Mbeya. Follow the track to the right and along to the end.

The second route to Mbeya Peak goes via the coffee-growing stronghold of Lunji Farm, near Mbalizi around 10 km west of Mbeya and 7km from Utengule Country Hotel, from where there are four different possible paths to follow up to the summit.

The walk takes around three hours up and two hours down, by the steepest route, and if arranged with Utengule they will often combine a trip to Lungi Farm and the peak with a visit to the Songwe Bat caves and Malonde Hot Springs nearby. This area is incredibly scenic, but also prone to hidden crevices and unusual rock formations, such as those that form the ‘bat cave’, and it is recommended that walkers take a guide.

The Uporoto Mountains

The driving route south of Mbeya is green and fertile and full of interesting off-road diversions. The tarmac route connecting with the Malawi and Mbamba Bay ferry service is excellently smooth and well finished, weirdly reminiscent of the Riviera scenery in ‘The Italian Job’, as the road neatly curves around the mountain edge with occasional impressive drops to either side.

This is an enjoyable driving route through constantly changing and impressive scenery – past volcanic mountains, crater lakes and waterfalls flowing over basalt rock, wending through bouncy tea plantations coloured a striking new-born green, and on down to the perennially lush and bountiful forests of the Livingstone Mountains – land of the Nyakusa people.

What to See in Mbeya

Ngozi Crater and Lake

The Ngozi Crater and Lake, just a short distance south of Mbeya, is the remains of an old volcano that has now collapsed to form a wide caldera filled with shining alkaline ‘soda’ waters. The waters of the lake are said to have magical medicinal powers. Ngozi means ‘the big one’; it stands at 2,621m.

Dedicated climbers are well rewarded with excellent views from the top of the sharp crater rim, from where the lake gleams below with an overwhelming tranquil air, and beyond the land is pocked with the points of smaller volcanic peaks. The walk to the rim leads through upland grasslands and tropical forests where families of Colobus monkeys chatter and play and a miasma of birds take refuge, and takes about an hour to ascend.

To reach Ngosi, take a right turn about 2km past the village of Isongole (Idweli), which lies about 33 km from Mbeya on Tukuyu Road. After 2km take the right-hand road when the road forks, and after almost 1 km further it will be necessary to leave the car and walk. It is well advised to leave someone with the car here, as a guard against break-ins.

The path leads into the forest for about 2.5km and then begins the climb to the crater top, just opposite a large, single tree. Just before the top, the path branches in two; the right-hand path leads swiftly to the peak, and the left leads down to the water’s edge, taking about half an hour to descend.

Photo credit: gumtau on VisualHunt

Mount Rungwe

Unlike Ngozi Crater, the volcanic cone of Mount Rungwe still stands, dominating the landscape to a height of 2,960m. The forests around Rungwe are still wild and unkempt, and almost entirely uninhabited by people, although there is a healthy population of colobus monkeys and other forest creatures.

The mountain can be climbed from the Kagera Estates timber camp, (turn left at Isongole onto the Kiwira Forest Station Road, and then right after 11 km, just before the Forest Station). However, this is only recommended during the dry months between June and November, or during a clear spell in February.

Follow the old road up on foot, and head right at the foot of the volcano – even though this path slants downwards initially.

An alternative climb is possible from the Rungwe Moravian Mission, from where it is worthwhile to take a guide to follow the complicated route from there to the top. Rungwe volcano remains active in parts, and hardened basalt lava flow is frequently passed along the way.

Marasusa Falls

The market town of Kiwira, (also called Mwankenja…), is 50 km from Mbeya on the Tukuyu road and lies close to the Kiwira River. The undulating land around this valley has formed several waterfalls and scenic watery rock formations close to the town.

The most accessible waterfall is just 4.3 km from the main road. Leave Kiwira on the road signposted to Igogwe Hospital, and follow the road over a bridge over the river. Turn left and cross the Igogwe stream, and then park and ask for directions to the Marasusa Falls.

The Marasusa falls are an impressive basalt drop, with several consecutive pools. They are popular for family washing sessions and provide a scenic rural setting for a picnic.

Ndulilo Falls

Reaching the Ndulilo Falls requires a less complicated driving route, but a more adventurous walking route, through a dark, bat-filled cave. To get there, park at the Igogwe Hospital and walk for 10 minutes to the river, where there is a sinkhole on the top of the south bank, where the river used to flow before it changed its path.

If you follow the sinkhole down you are liable to disturb a few sleepy bats, but will eventually reach the base of the falls.

Daraja ya Mungu

The wonderfully named Daraja ya Mungu (Bridge of God) is an inspiring stretch of rock arching over the rushing river, which has eked its stoic pathway beneath. The rock over which the lava flows is estimated to date from the Pre-Cambrian period, approximately 1800 million years ago.

Unfortunately, the most impressive feature of the water and rock phenomena in this region has evolved too close to a temperamental, military-run Prison College for complete comfort. You can visit Daraja ya Mungu, but the proximity of this erstwhile school of learning means that the road closest to the bridge has been iron-fenced and covered in signs prohibiting photography, and beware the wrath of ranting officials who find you bending the rules!

To get there, turn right at a tiny village, just before Tukuyu, on a corner approximately 7 km from Kiwira. The road is pretty good, as a hydroelectric power station was planned here, and of course, there is the college.

It is best to follow the road around until the bridge can be seen, then park and walk down the incline from there. There are many interesting features around this region, but it is now harder to access the nearby hole where the river falls into a rock ‘cauldron’ known as Kijungu (Cooking Pot) because the Prison College insists that you must acquire a permit.

The view is especially pretty as the sun sets, and the land around is mainly picturesque until you reach the college.

Tukuyu

The small town of Tukuyu perches on top of the Ntukuyu volcano, almost halfway between Mbeya and Lake Malawi (formerly Lake Nyasa) at an altitude of 5,300ft. Its elegant vantage point makes it most worthwhile for the views that it affords of the surrounding countryside.

The town flourished in importance for a while during the German era and earned the name Neu-Langenberg for a short period after 1901, when it became the centre for German administration in the region. This followed the demise of their previous headquarters on the Lake, Alt-Langenberg, after the doctor died of malaria there.

Hiking in Tukuyu

If you are planning a leisurely foray through the mountains it is probably worth fixing up some accommodation, either at Tukuyu or on the shores of Matema Beach on Lake Malawi, as a round trip including walks and diversions will take at least two days. The accommodation possibilities in each of these are very basic, although slightly nicer on Matema Beach.

The great range of the Livingstone Mountains southeast of Tukuyu is the result of extreme rift action that would have occurred before the volcanic eruptions in the region; Lake Malawi lies on the rift floor. As a result, there are a number of good alternatives for trekking in this region, both north of Tukuyu around the features mentioned above, or south, around Masoko Crater Lake.

Masoko Crater Lake is an impressive old volcanic crater 19 km south of Tukuyu, now covered in lush vegetation. A short walk through the trees takes you to the water’s edge, where it is possible to swim, and some old coins from the German era have been found (and sold) along the way.

The crater lake is just off the eastern road from Tukuyu, which also passes Kalambo Hot Springs en route to Ipinda (not to be confused with Kilambo Hot Springs before Kyela, below). This is a far more dusty and less smooth route towards the lake than the western road, which has a smooth tarmac surface almost all the way through Kyela to the port at Itungi. About 8km down this fine westerly road you come to the village of Ushirika, (also signposted Mpuguso…)

Where to Visit Near Tukuyu

Kaporogwe Falls

Good walking and swimming possibilities are found close to here (but require a 2km walk!) at Kaporogwe Falls. To find them, turn right at Ushirika following signposts to Kaporogwe, and then follow signs to the Leprosarium – where it is possible to get permission to park vehicles – then walk past the buildings and head down the hill beyond, continuing straight on for about 2 km.

This brings you to the top of the falls, where a precarious bridge crosses behind a pretty Gardenia tree to a good picnic area and vantage point over the falls, sheltered beneath an impressive overhanging slab of basalt. It is also possible to climb down the falls, with care, find routes into caves behind the curtain of water plummeting down before you, and swim in the pool beneath.

Kilambo Hot Springs

Continuing southwards, 44 km from Tukuyu and just before Kyela, a signpost points left to Kilambo Hot Springs. These are definitely springs and not pools – entertain no illusions of therapeutic bathing! – but the track leads right to the springs at the base of the hillside, and the surrounding woodlands are a haven for orchids.

Matema Beach

For relaxation and quiet, it is better to abandon the small town of Kyela for Matema Beach, where there is fine accommodation almost at the water’s edge, plenty of fresh fish and wide open views.

The thick, golden, granular bay of Matema is lapped by the fresh waters of Lake Malawi and provides a refreshing point for quiet contemplation in the lea of the Livingstone Mountains, which run down to the eastern shore of the lake. It is a rural region where the focus of activity is fishing and the chores of daily life – mending fishing nets, repairing local dug-out canoes, preparing for night-time excursions – yet it seems that most people along the beach have time for a chat.

The land here is hot, a strong contrast from the volcanic mountains behind you, and to the east and west, and much life on Matema is spent seeking shade after mid-day. Sunburn is a regional hazard for visitors with pale skin.

Photo credit: paulshaffner on VisualHunt.com

Matema

Matema provides a good central base for exploring the local countryside and mountains, which give a cool cover from the sun. The beach is approached through stunning forested regions, where dense greenery and thickets conceal clusters of Nyakyusa houses, many of which demonstrate inspired building methods involving complex palm weaves and raised platform storage huts for pots, chickens, water and grain.

A number of these have also been painted and decorated with unique designs and images, apparently drawn with local dyes. There are also plenty of fine earthenware pots in evidence in every household and fireplace, generally the product of the Kisi people who also live in this area and are famed throughout Tanzania for their clay-working skills.

These pots are sold wholesale from Ikombe, south of Matema, where you may also have the chance to see them being made in Matema itself on the Saturday morning market, for which they are shipped from Ikombe by canoe. They are also often found sold for extremely good value at morning roadside stalls between Matema and Mbeya. From here they are exported to Arusha, Iringa and Dar es Salaam, and increase in price with distance!

Iringa

The town of Iringa nestles on a 1600m plateau at the heart of the Southern Highlands, almost entirely hidden from view until you come upon it. It is an unusually attractive town, with wide streets lavishly lined with flowering jacaranda – a legacy of its colonial origins.

An overall impression of the town is one of clean organisation and investment – all major roads throughout were immaculately re-gravelled and resurfaced in 1999 – and the central market is vibrant, busy and amply piled with fresh, colourful goods. The high-altitude climate has attracted a healthy population of expatriates, many of whom have returned to the area as a result of the extensive tea plantations further south at Mufindi, and continue to nurture business interests in the town.

There are a number of pleasant hotels and restaurants as a result and a thriving Christian community. A grand cathedral is raised high on the hill at the entrance of town, its brick façade and whitewashed knave and aisles beneath a neat tile roof form an imposing feature against the Iringa skyline.

History of Iringa

Iringa town was developed following the eventual victory of the German colonists over the Hehe tribe and its supporting sub-tribes during their valiant resistance to European rule through the 1890s. This resistance was spearheaded by the infamous Hehe Chief Mkwawa, whose formidable war cry is thought to have inspired the naming of the tribe.

The Hehe reputation for warfare was already well established among neighbouring tribes before that advent of the colonial era, and Mkwawa had established a formidable fortress at Kalanga – just a few kilometres outside Iringa, now on the road into Ruaha National Park – with outer walls measuring 13 km end to end. The walls are said to have been ‘4m high and as wide as a road’, and contained a smaller, also fortified, inner courtyard.

Mkwawa’s tribe practised archery with poisoned arrows, and these became a worthy deterrent for groups of slave-raiding Arabs, until he secured their allegiance with supplies of ivory and leopard skins instead. But no such alliance was made with the European colonialists, who remained irreconcilably at odds with the warrior-like Hehe and their supporting sub-tribes.

Mkwawa’s men made a lasting impression on the German troops in 1891 when they ambushed Lugalo outside Iringa and trounced the colonial forces. Humiliated and furious, the Germans retreated to regroup and plan their retaliation.

Three years later, in 1894, they returned for a rematch and successfully destroyed Mkwawa’s fort. Now the remnants of this ancient rock and clay-moulded stronghold have been whittled down to a rather large mound in the middle of Kalenga village, from the top of which Mkwawa was said to have addressed his people.

The vague outline of the old fort walls can just be made out around the edge of a sun-scorched football pitch, but the final onslaught of bullets and grenades launched by German troops from the top of a nearby hill comprehensively obliterated the fortress.

On the 19th of June 1899, after seven years of resistance, Chief Mkwawa shot himself through the skull rather than surrendering to his German foe. Somewhat ungraciously, the thwarted colonialists chopped his head off and sent it back to Germany, where it came to rest in the Bremen Anthropological Museum for more than fifty years, gathering dust and hardly considered. But the Hehe did not forget and continued to demand its return, until, on the 19th of June 1954, it was finally returned to Mkwawa’s grandson, Chief Adam Sapi.

June 19th has traditionally been a holiday for the Wahehe, involving everyone drinking a popular brew of fermented millet and maize and contributing a cow or money for the celebrations. Although this memorial was forbidden by the original dictate of the 1967 Arusha Declaration concerning distinct tribal practices, it has recently been reinstated since the centenary of Chief Mkwawa’s death.

Chief Mkwawa’s skull is now on display in the small memorial museum on the outskirts of Kalenga village. The path of the final bullet is revealed from chin to crown.

Entrance to the museum is arranged by the caretaker, presently Francis Kalenga, who provides a detailed and amusing account of the local history in return for a donation of around Tsh 1000 each. Even if you turn up and find the place locked and apparently deserted, any of the children that slowly materialise from the shade of the trees can be willingly dispatched to find the caretaker and the key, especially if showered with rewards on their return!

To the right of the museum, you can see the impressive ‘palace’ built by the Wahehe people to honour their Chief and his family, even though their rule became only nominal after Independence and the devolution of tribal powers. The ‘palace’ looks surprisingly similar to an English country estate house and was built on the proceeds of a collection taken from each member of the tribe.

Mkwawa’s grandson, Adam Sapi, was the Speaker of Tanzania’s first parliament and a highly regarded politician. He died in June 1999, and his son, Mfuimi, takes on the nominal role as head of the Hehe.

What to Do In Iringa

Iringa is small and friendly enough to explore on foot in a day, with a few interesting old colonial buildings such as the Old Boma, Town Hall and Hospital and a bustling although fairly typical local market. A monument outside the police station commemorates the native warriors who died in the Maji Maji rebellion.

Gangilonga Rock

A good destination to the North of the town is Mkwawa’s favourite spot for meditating, known as Gangilonga Rock, or the ‘Talking Stone’ in Wahehe. It takes a few minutes to climb to the top, with good views of the town once there. The surrounding area provides good walking opportunities, with views over the surrounding plains from the plateau.

Isimila Stone Age Site

Just outside Iringa, Isimila Stone Age Site is considered one of the most exciting areas for Stone Age archaeological findings in East Africa. The site is a dry lake bed, and was discovered in 1951, by a schoolboy who came across an axe head.

It is thought that Stone Age man camped on the shores of the lake and shaped and worked his tools here, based on the prolific number of tools found in the area and several blocks and boulders that were probably used to shape the granite and quartzite rock. A number of fossilised bones have also been found showing the prehistoric forms of species of elephant, hippo and giraffe.

The site is signposted from the main road to Mbeya just less than 20 km (12 miles) south of Iringa. The site’s office and small museum are about 1 km further from this turning and house an exhibition of some of the tools, bones and fossils found in the area that are thought to date from around 60,000 years ago.

There is a $2 entry fee. A guide can also take you around the site on a walk that takes about an hour.

A short walk along the valley brings you into the Isimila Gully, a scenic red earth area that has been naturally sculpted and eroded into impressive sandstone pillars and eerie formations that loom overhead on each side of the valley – a good spot for a picnic! A taxi from Iringa will cost around $20, or take a dala-dala in the direction of Tosamaganga and get out at the Isimila turn-off.

Kalenga

The small village of Kalenga is just a short drive from Iringa town and makes for an interesting venture if you have a yen to see the tiny memorial museum to Chief Mkwawa of the Hehe. From here it is also possible to cast an imaginative eye over the sandy remnants of his fortress, now more obviously a football pitch with hummocks of earth around the edge.

If you’re looking to plan a trip to any of these destinations in Tanzania’s Southern Circuit, Tanzania Odyssey is a specialist tour provider that can help you plan a tailor-made holiday. We work with trusted partners and hand-picked accommodation providers to offer our guests incredible experiences in this African country, from classic safaris to relaxing beach trips.

Take a look at our trips near Ruaha National Park or get in touch to find out more about how we can help.